Blog

16 days of activism: Recognising the impact of Covid-19 on women’s experience of gender-based violence.

This week marks the beginning of the 16 days of activism against gender-based violence. The campaign starts on the 25th of November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The focus of this year’s campaign is the impact Covid-19 has had on women’s experience of gender-based violence. The theme places a strong emphasis on prevention, ensuring essential services for victim-survivors and greater data collection to improve services for victim-survivors.

Violence against women (VAW) occurs at alarmingly high rates and impacts all aspects of women’s lives. In the beginning months of the pandemic, self-isolation and social distancing measures led to increased risks for victim-survivors of domestic abuse, essentially trapping them in unsafe situations with limited access to support and opportunities to leave. It’s important to understand that domestic abuse is not increasing due to Covid-19 but rather that existing abusive relationships are intensified during this period. Domestic abuse is not a one-off incident. It’s a pattern of controlling, coercive, threatening and/or violent behaviour that often includes physical, emotional, psychological and economic abuse.

With homeworking continuing to be prioritised by public health guidance and with the recent introduction of tier 4 restrictions for 11 local authorities, many victim-survivors may still be facing significant barriers in accessing support.

Covid-19 has highlighted the integral role of employers in supporting victim-survivors. For some women, work may be a safe space and a vital link for accessing support from colleagues or specialist services.

The significant changes to the workplace since the Covid-19 outbreak, including an increase in homeworking, employees working fewer hours, scaled back workforces and a reliance on digital platforms for communication, have affected the way women experience VAW. For example, digital platforms have been essential for enabling homeworking, but they have also provided perpetrators with greater access to women that wasn’t available before, for example, the ability to see when colleagues are online, or ability to send private messages or pictures constantly through the day. This has resulted in increased cases of cyberstalking and sexual harassment that have become inescapable at home.

This year’s 16 days of activism campaign is an opportunity to raise awareness of the significant barriers that victim-survivors face in doing their jobs effectively and accessing support. It’s also an opportunity to encourage employers to adapt workplace practices to better support victim-survivors. In many cases, line managers and colleagues may be the most consistent contact for victim-survivors and it’s essential that they’re aware of how to recognise the signs of VAW and initiate a conversation.

As part of Close the Gap’s Equally Safe at Work employer accreditation programme, we developed guidance on VAW, Work and Covid-19 for local authorities which outlines best practice for responding to and supporting employees disclosing or reporting VAW. Equally Safe at Work has enabled councils to develop a range of employment practices that support victim-survivors at work.

For this year’s 16 days campaign, we’re sharing the learning from Equally Safe at Work and are highlighting best practice tips for line managers in any organisation.

- If you have a VAW policy, raise awareness of your policy and what your organisation can do to support victim-survivors.

- During periods of lockdown, offer victim-survivors a key worker letter, where appropriate, to enable them to come into the office. This should be discussed with the victim-survivor and only provided if they want it.

- During periods of lockdown, ensure you remain in regular contact with all staff, including those on sick leave, through catch-ups or 1-2-1s.

- Familiarise yourself with the signs that an employee may be affected by a form VAW during Covid-19 (this can be found in the Equally Safe at Work guidance on VAW, Work and Covid-19).

- Initiate a conversation if you suspect an employee may be experiencing a form of VAW. Some victim-survivors may not want to disclose their experience, and this should be respected. To start the conversation, you may want to ask how they feel about changes in their work environment or ask if everything is alright at work or at home.

- Be supportive and non-judgemental if one of your team discloses.

- Go at the employee’s pace and if she’s finding it difficult to speak or is becoming distressed, suggest taking a break.

- Work with the employee to identify their support needs and the simple changes that can be made to support her.

- For employees affected by domestic abuse, stalking and/or so-called “honour-based” violence agree a safety plan in line with the staff member’s needs.

- For victim-survivors of domestic abuse, agree code words so they are able to communicate safely about their situation. This can be particularly important for employees who are homeworking and live with the abusive partner.

- Protect their confidentiality and communicate to them how you will do that.

- Discuss whether other workplace policies could be used to support them. This could include identifying whether staff would like to work flexibly, adjust work hours or workload, wherever necessary and possible.

- Organise regular meetings to check in and review their support needs.

- Signpost to local specialist services, such as Women’s Aid and Rape Crisis (You can find more links to support services here).

There is additional support available for SMEs through Close the Gap’s free online self-assessment tool, Think Business, Think Equality. Think Business, Think Equality enables businesses to assess their current employment practice and provides tailored advice and an action plan which supports SMEs to realise the benefits of gender equality. Think Business, Think Equality has guidance on how to support victim-survivors of domestic abuse during Covid-19. The guidance accompanies additional resources on domestic abuse which includes an FAQ on domestic abuse and work, good practice examples, and workplace resources.

Find out more by taking the Think Business, Think Equality test on domestic abuse at www.thinkbusinessthinkequality.org.uk.

Equal Pay Day 2020: Why it’s important to look beyond the headline figures

Equal Pay Day is the day from which women are effectively working for free for the rest of the year because of the gender pay gap. Of course it's much earlier in the year for Black and minority ethnic women and disabled women, who experience higher gender pay gaps.

New data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that Scotland’s gender pay gap has narrowed from 13.3% to 10.4%. This ostensibly suggests that progress on women’s workplace equality has been made. However, evidence from elsewhere shows otherwise, as women’s employment has been disproportionately negatively affected by COVID-19 in a range of significant ways.

While the latest data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings shows a reduction in the gender pay gap, it comes with reliability warnings with a quarter of the usual sample of employer pay data missing and the impact of COVID-19 job disruption on this data remains unclear.

COVID-19 illuminates the challenges in accessing good quality gender-sensitive, sex-disaggregated labour market data. Intersectional labour market data remains almost entirely non-existent, which makes it extremely difficult to get a granular understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on different groups of women, and the effect on women’s and men’s labour market participation.

The data that is publicly available makes for a somewhat confusing picture. UK Government data relating to the Job Retention Scheme contains minimal gendered data, and the Scottish Government’s gendered data on job disruption is patchy at best. The data tells us that the picture on gender and furlough in Scotland is complicated, and constantly changing.

For example, the headline data shows that, overall, more male employees have been furloughed than female employees. However, since the 1st of July, more women have been furloughed than men across the UK which would imply that women have been furloughed for longer than men. The headline figures therefore mask the nuances of job disruption and furlough.

Moreover, ONS data shows a sharp increase in women working full-time. Compared to this time last year, 41,000 more women are working full-time which is likely to have a narrowing effect on the gender pay gap. By contrast, 27,000 fewer men are working full-time, and 11,000 more men are working part-time when compared with this time last year. The impact of changes in male working patterns on the gender pay gap will depend on whether more men are now earning lower part-time hourly rates, or merely working reduced hours on the same rate of hourly pay. This is unclear from the data. Regardless, men’s average hourly pay will also have been reduced as a result of furlough which will artificially deflate the overall gender pay gap figure temporarily.

The analysis which accompanies these data releases is not gendered, which not only creates an additional challenge in interpreting the data, but also serves to highlight the lack of gender analysis in labour market policymaking.

COVID-19 has had an unprecedented effect on the labour market, and women’s employment specifically, with the medium and long-term effects yet to be seen. This year’s gender pay gap underscores why it’s necessary to look beneath the headline figure. The reduction is very likely to be masking the relatively recent gendered effects of COVID-19 on women’s employment that will not yet be captured by the gender pay gap which is a lagging indicator.

Equal Pay Day once again highlights the importance of quality gender-sensitive, sex-disaggregated labour market data. In the coming weeks, Close the Gap will be publishing our annual analysis of gender pay gap statistics which will take a deeper dive into this year’s data. Meantime, you can read last year’s gender pay gap statistics paper here.

The Living Wage is key if we are to tackle women’s in-work poverty

Living Wage Week is an opportunity to recognise the importance of the Living Wage in tackling women’s poverty and realising fair work for women. Women account for the majority of low-paid workers in Scotland, and two-thirds of workers being paid less than the Living Wage are women. Low pay is a critical factor in the gender pay gap and also reflects the continued undervaluation of “women’s work” in sectors such as social care and childcare.

Women are more likely than men to have caring responsibilities and therefore must find work that allows them to balance earning with caring. This sees women concentrated in part-time work which contributes to women’s higher rates of in-work poverty as most part-time work is found in the lowest paid jobs and sectors. Part-time jobs are more than three times as likely to pay below the Living Wage than full-time roles and research from Living Wage Scotland found that women in part-time work stand to benefit the most from Living Wage accreditation.

This year, Living Wage Week is more important than ever. Evidence highlights that low-paid women have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 job disruption. Low-paid women are more likely to work in a shutdown sector, are less likely to be able to work from home, and are more likely to lose their job over the course of the crisis. For women earning less than the Living Wage, receiving only 80% of their usual salary through the Job Retention Scheme is likely to push them into further and deeper poverty.

Many of the sectors where women are concentrated that have been particularly impacted by shut downs and physical distancing measures, such as retail and hospitality, are notoriously low paid and characterised by job insecurity. For example, four in ten of those working in retail and wholesale are paid less than the real Living Wage and 80% of people working in hospitality reported that they were already struggling with their finances before going into lockdown. Women in these low-paid, high-risk sectors were already more likely to be experiencing in-work poverty and are therefore less likely to have savings to fall back on.

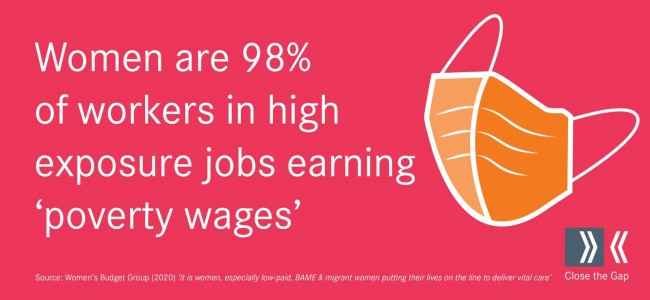

In addition, the majority of the key worker jobs identified by the Scottish and UK Governments are undervalued female-dominated occupations including nurses, carers, early learning and childcare workers and supermarket workers. These roles are predominantly done by women, and for this reason many of these jobs are systematically undervalued in the labour market. Research by the Women’s Budget Group’s found that women account for 98% of the workers in high exposure jobs earning ‘poverty wages’.

Women who were already struggling are now under enormous financial pressure, being pushed into further and deeper poverty. Ultimately, without specific interventions to promote women’s equality and a gendered response to the crisis, COVID-19 will exacerbate the gendered nature of poverty in Scotland.

Last week, in response to the impact of COVID-19 on young people’s employment prospects, the Scottish Government launched the Young Person’s Guarantee. Close the Gap has advocated that gender is integrated into the Guarantee, that the barriers young women face in entering the labour market are recognised, and that occupational segregation is proactively challenged. We’ve therefore welcomed the commitment from the Scottish Government that the design of the programme will ensure all groups of young people will benefit from the Guarantee. While employers engaged in the scheme must commit to the payment of the Living Wage over a set period of time, there is no obligation that employers pay young people at this rate from the outset. As the payment of the Living Wage is critical to tackling women’s poverty, particularly for young mothers, it is vital that the Government’s ambitions around the Living Wage are realised by employers engaged in the Guarantee.

The Scottish Government have acknowledged the inextricable links between gender and poverty, and women’s poverty and child poverty in a number of key policy documents including Scotland's gender pay gap action plan, and the child poverty delivery plan. These plans are clear that tackling the gender pay gap is essential to overcoming women’s higher rates of in-work poverty, and child poverty in Scotland. In particular, the Child Poverty Delivery Planhas a focus on engaging with sectors such as tourism, retail and hospitality where women’s low pay is a concern. In outlining how these sectors have a critical role to play in tackling child poverty, the plan establishes that the payment of the Living Wage in female-dominated sectors is vital to lifting women and their children out of poverty.

In response to COVID-19, achieving fair work for women by building a labour market and economy that works for women must be core to economic recovery policymaking. Of course, while the payment of the Living Wage in female-dominated jobs and sectors is an important starting point, this also has to be accompanied by a more structural response to the continued economic undervaluation of work done by women.

Prior to the crisis, women were more likely to be experiencing in-work poverty. This trend will only be worsened by the labour market and economic implications of COVID-19. This makes it even more vital that economic recovery policymaking and action to address child poverty prioritises substantive action on women’s low pay. The Living Wage ultimately remains key to tackling women’s in-work poverty.

We're hiring!

Communications and Administration Assistant

Close the Gap is recruiting for the role of Communications and Administration Assistant. The successful applicant will be responsible for co-ordinating Close the Gap social media channels and websites, supporting wider communications work and providing administrative support.

We’re looking for an enthusiastic person with professional social media experience and strong communication skills to contribute to the delivery of Close the Gap’s work. Committed to women’s labour market equality, you’ll provide administrative support, contributing to the effective running of the organisation. You’ll also be working within our small, busy team to assist with the development of communications, events and publications.

Hours: 28 hours per week

Salary: £17,138 (FTE £21,423)

Pension: 10% employer contribution

Location: 166 Buchanan

Street, Glasgow, G1 2LW (homeworking while Covid-19 lockdown measures are in

place)

Responsible to: Policy Manager

The post is fixed term, funded until 30 September 2021, with potential extension depending on funding.

Close the Gap values diversity in our workforce, and encourage applications from all sectors of the community. Flexible working options are available for this role.

Read the job description, person specification and other application information.

How to apply

Electronic applications must be submitted using our online application form which you can find on our website at closethegap.org.uk/jobs. If you are unable to use an online application process please contact us at info@closethegap.org.uk

The deadline for applications is 12pm Monday 7 December 2020.

You will be notified by Tuesday 22 December 2020 if you have been selected for interview.

It is anticipated that the interviews will take place remotely during the week commencing Monday 11 January 2021.

New guidance for local government on supporting women at work during Covid-19

Covid-19 has had a drastic impact on women’s experience of employment. The majority of key workers are women, working in often economically undervalued and lower paid female-dominated jobs. In local authorities this includes carers, cleaners, catering workers and early learning and children workers. Many have had to manage the immense pressures of providing essential services during the pandemic while also trying to care for children and other family members.

Without mitigating action Covid-19 will have long term consequences for women’s employment which exacerbates women’s inequality at work. It’s critical for employers to recognise the disproportionate impact Covid-19 has had on women, especially different groups of women. For example, BME women, single parents, and younger women have been particularly affected as they are more likely to work in a sector affected by job disruption. An intersectional approach to workforce planning is necessary to ensure the distinct experiences of different groups of women are visible.

Employers must act to support women workers

As organisations adapt to new ways of working, it’s essential that women’s experience of employment and Covid-19 is used to inform planning for the new normal. There’s a considerable risk that progress on women’s equality at work will be rolled back. Now is the time for employers to demonstrate their commitment to gender equality. Not only is it necessary to support women workers, but there’s clear evidence that gender equality is a catalyst for growth and recovery.

We developed guidance for councils who are participating in Equally Safe at Work on best practice for ensuring women’s inequality isn’t further exacerbated by Covid-19. The guidance provides information and actions for councils on:

- data collection;

- caring responsibilities;

- flexible working;

- homeworking;

- health and safety;

- undervaluation;

- pregnancy and maternity; and

- violence against women.

Covid-19 has magnified the gendered barriers in the workplace. Our new guidance will enable employers to better support women returning to work or continuing to work from home safely. It also supports employers to review data gathering to make sure they’re capturing women’s different experiences during Covid-19, and highlights where changes need to be made to employment practice to ensure women’s equality and safety.