Blog

Scot women shout out

Women’s campaign groups, equalities organisations, and individual gender advocates in Scotland do amazing things, often with very limited resources, and little attention. We are planning to highlight some of the people and groups making women’s equality happen, to celebrate their work and inspire others to take action. We’ll be doing this on Monday using the hashtag

#ScotWomenShoutOut

We are hiring!

Close the Gap is hiring!

We’re looking for an enthusiastic person with strong organising skills to provide administrative support to contribute to the effective delivery of Close the Gap’s work. Committed to women’s labour market equality, you’ll be working within our small, busy team and also supporting the development of our policy and project work.

There's some further information on the role below, including closing and interview dates, and a link to the application pack.

Development Assistant

Salary: £20,000 (plus 10%

pension)

Hours: 34 hours per week

Location: The post is based in Glasgow city centre at 166 Buchanan Street.

Close the Gap is committed to being an equal opportunity employer, and we welcome applications from all sectors of the community. Flexible working options are available for this role.

The post is fixed term, funded until 31 March 2020.

Organisation profile

Close the Gap is Scotland’s national policy and advocacy organisation working on women’s labour market participation. We work strategically with policymakers, employers and unions to address the causes of women’s inequality at work. We have been operating since 2001.

Application notes

You can download the application pack and equalities monitoring form here:

Development Assistant application packCompleted electronic applications must be sent to: info@closethegap.org.uk.

You may also return your application by post to:

Recruitment

Close the Gap

Third Floor

166 Buchanan Street

Glasgow G1 2LW

The closing date for all applications is Friday 18 May 2018. Interviews will be held on Monday 4 June or Tuesday 5 June 2018. You will hear from us by Monday 28 May 2018 if you are being invited to interview.

We value diversity in our workforce, and welcome enquiries from everyone.

Our accreditation programme will ensure women are Equally Safe at Work

Close the Gap is pleased to announce that we are developing an employer accreditation programme to support the implementation of Equally Safe, Scotland’s violence against women strategy. Equally Safe critically recognises that gender inequality is a root cause of violence against women and addressing labour market inequality is a necessary step in ending violence against women. The employer accreditation programme will be initially piloted in a diversity of local authorities across Scotland, with the view of a larger roll out in the future.

From research conducted by Close the Gap, we found that there are no employer accreditation programmes focusing on gender equality at work and violence against women at work in Scotland or the UK, revealing a clear gap in provision. This programme will enable local authorities to demonstrate good practice and show leadership in addressing violence against women. It also provides the opportunity for employers to make the connection that preventing violence against women starts with advancing gender equality.

Equally Safe recognises that employers have a key role to play in supporting victim-survivors and tackling perpetrators because violence against women is a employment issue whether it occurs inside or outside of the workplace. UN Women and The International Labour Organisation (ILO) have stated that violence against women results in greater economic and social inequalities, disrupts economic empowerment of women and entrenches negative stereotypes against wom

Women comprise 68% of the local government workforce in Scotland, but are concentrated in undervalued, low-paid jobs such as homecare, admin and cleaning, and under-represented in management and senior positions. As a result, women have reduced financial independence, restricted choices in employment and in life, and greater economic inequality which creates a conducive context for violence against women. Financial dependence and poverty are both primary risk factors that diminish women’s resilience and options in the face of violence.

Women also directly experience violence and harassment at work. Research by the TUC found more than half (52%) of women reported having experienced sexual harassment in the workplace, with this figure rising to two thirds of women aged 18-24. The research asked women about the different types of sexual harassment they had experiences, which ranged from unwelcome sexual comments to serious sexual assaults. Research by Zero Tolerance found that 70% of respondents had witnessed or experienced sexual harassment. Most women (80%) who experience sexual harassment in the workplace will never report it.

Violence and harassment that happens outside of the workplace, such as at home, can significantly impact how women engage with paid work. An evidence review conducted by Engender found that in the UK and around the globe that experiencing domestic abuse can have a profound impact on whether women work in the formal labour market, the work that they do, and their experience of work. This also has an impact on employers and can lead to reduced productivity, loss of skills and talent, and absenteeism. The economic cost of domestic abuse is estimated to be over £1.9 billion a year, a result of decreased productivity, administrative challenges from unplanned absences, lost wages and sick pay. Taking action and supporting staff is not only a reflection of good practice but also corporate social responsibility.

Employers have a vital role to play in advancing gender equality and challenging violence against women. They can develop employment policies and practice that are sensitive to the needs of victim-survivors, take action to prevent violence against women at work, and take account of women's difference experiences in all aspects of the workplace.

The next steps for Close the Gap on this project are to look at international best practice and work with leading experts and stakeholders in implementing and developing the accreditation programme.

Close the Gap assessment of Scottish gender pay gap reporting suggests most employers are not planning to take action to close their pay gap

So, (most of) the results are in, and it’s not looking good. Close the Gap has done an assessment of gender pay gap reporting by Scottish employers. We looked at a cross-sectoral sample of 200 Scottish employers[1] across Scotland to get a more granular picture of the pay gap at the enterprise-level but importantly to identify what employers plan to do to close their pay gap. We used data published by organisations on the UK Government’s gender pay gap viewing service.

The headline findings from the assessment found:

- Extremely high gender pay gaps of up to 60% in male-dominated sectors such as construction, finance and oil and gas;

- Staggering gender gaps in bonuses of up to 607% in male-dominated sectors such as manufacturing, construction, energy and finance;

- Less than a third of employers have published a narrative which explains the causes of their pay gap, with many superficial in their analysis;

- Less than a fifth of employers have set out actions they will take to close the pay gap, with many actions unmeasurable and unlikely to create change; and

- Only 5% have set targets to reduce their pay gap.

Many employers explain their pay gap by glibly stating that it’s because more men are in senior roles and that is justification. That women are under-represented in the upper echelons of large companies is a critical problem, but also important is women’s persistent concentration in the lower-paid jobs in all organisations. A lack of quality part-time and flexible working means that many women who require to work part-time to accommodate their caring roles become boxed in, unable to progress into overwhelmingly inflexible senior roles, and end up working below their skill level. The under-utilisation of women’s skills is a drag on growth, contributing to sector-wide skills shortages. Research by Close the Gap established that equalising the gender gap in employment could add up to £17bn to Scotland’s economy.

Almost entirely missing from the current discussion of the pay gap is gender. Studies which have modelled the pay gap, including Close the Gap's recent modelling of Scotland's gender pay gap, has consistently found that gender itself is the largest contributing factor to the pay gap. This is most commonly explained as straight-up gender-discrimination in the labour market.

That less than a third of Scottish employers have set out an action plan for closing their pay gap is worrying but perhaps not surprising. It reaffirms our concerns about the limitations of the gender pay gap regulations. While we’ve welcomed the new pay transparency measures as an important first step in addressing the systemic inequality women face at work, the fundamental weakness is that employers aren’t required to take action that will close their pay gap. Evidence shows that most employers are unlikely to voluntarily take action on gender equality, predominantly because they unduly think they’re already treating all their staff fairly.

We know from the experience of the Scotland’s public sector that reporting alone doesn’t create change. Employers need to look beneath the headline figure, analyse their pay data, identify why there are differences and then set out the actions they’re going to take to solve the problem.

The challenge for employers is to decide whether to be sector leaders and demonstrate their commitment to gender equality, or to risk reputational damage by doing nothing.

We’re going to be using our findings to inform our work on the pay gap with employers and policymakers. We’ll also be continuing to support employers who are doing work to close their pay gap, primarily through our free online pay gap reporting tool, Close Your Pay Gap.

You can read a summary of the findings here.

[1] UK Government estimates that there are around 700 Scottish private and third sector organisations required to report their gender pay gap information.

The Gender Penalty: Close the Gap's new research on Scotland's gender pay gap

The current level of discussion around the pay gap is unprecedented as the deadline for large companies reporting their pay gap gets ever closer (just under two weeks to go, in case you wondered). At our conference in February, we launched our new research The Gender Penalty: Exploring the causes and solutions to Scotland’s gender pay gap.

The pay gap is a defining feature of Scotland’s labour market and although it’s very slowly narrowed over the longer term, progress has stalled in recent years. This is borne out as the pay gaps of well-known companies are hitting the headlines on a daily basis.

A range of studies have modelled the pay gap at a UK level, most notably the seminal work by Wendy Olsen and Sylvia Walby for the Equal Opportunities Commission. But there wasn’t any Scottish specific research on the factors driving Scotland’s pay gap. So Close the Gap commissioned University of Manchester to do an economic modelling of Scotland’s pay gap which would identify the causes, and look at how these have changed since 2004.

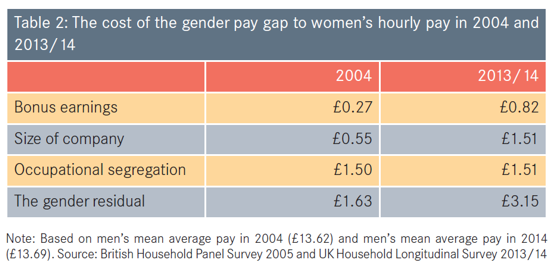

The research found that there are four main drivers of Scotland’s pay gap: bonus earnings, the size of company a woman works for, occupational segregation, and something called the “gender residual” which is most commonly attributed to gender discrimination in the labour market.

Perhaps most alarming is that there’s been no improvement in the causes since 2004, and the effects of most of the causes have actually worsened. Occupational segregation is seemingly an intractable problem, with no progress made. The effects of bonus earnings and company have tripled, while the effect of the gender residual has doubled, now costing women a staggering £3.15 per hour.

The new report also examines responses to the pay gap, and sets out what needs to change to advance equality for women at work. What’s clear is that existing approaches to the pay gap are failing to deliver change. Policy responses have been complicated by the devolution settlement whereby Scottish and UK Governments both hold powers for levering change. While employment and anti-discrimination law are reserved to Westminster, Holyrood has power over a wide range of policy domains that are instrinsic to closing the pay gap including early years, primary and secondary education, further and higher education, skills, economic development, employability, childcare, long-term care, the public sector equality duty and procurement.

There’s never been a cohesive, strategic approach to solving the problem which is why we’ve called for a national strategy to close Scotland’s pay gap. In its inquiry into the economic gains of closing the pay gap, the Scottish Parliament Economy, Jobs, and Fair Work Committee made the same call.

The pay gap is a structural problem which requires action from a wide range of stakeholders. We’ve therefore also made a wide range of recommendations in the report for key stakeholders including Scottish Government, the enterprise agencies, Skills Development Scotland, Education Scotland, employers and unions. The time for change is now.

Read the full report here.