Blog

Challenge Poverty Week: What COVID-19 means for young women’s in-work poverty

One of the themes of this year’s

Challenge Poverty Week is work and jobs, with the key message that tackling

poverty requires investment in decent work. This is particularly important for women,

as women’s experience of the labour market is

directly linked to their higher rates of poverty. This means women’s concentration in low-paid,

undervalued work is a key cause of women’s increased likelihood of experiencing

in-work and persistent poverty.

This year, these issues are more pertinent than ever with COVID-19 job

disruption having a disproportionate impact on low-paid women, Black and

minority ethnic women and young women’s employment. This is particularly

significant as these groups of women were already more likely to be

experiencing in-work poverty prior to the crisis. COVID-19 has therefore placed

these women, and their children, at even greater risk of poverty, adding to a

growing child poverty crisis.

Evidence from previous economic crises also indicates that economic downturns tend to have particularly detrimental effects on younger workers. Certainly, the economic and labour market consequences of COVID-19 have had a disproportionate impact on young women’s employment and financial wellbeing, with these trends only likely to worsen over the course of the crisis.

Close the Gap’s Disproportionate Disruption analysis highlights that, because of occupational segregation, young women are more likely to work in a shutdown sector such as hospitality and retail; younger women are at particular risk of furlough; women in low-paid jobs will be particularly affected by job disruption, placing them at greater risk of poverty; and, as per previous recessions, younger women are more likely to lose their job.

Data shows that young women are more likely to have been furloughed, with 65% of female employees aged 17 being furloughed. Women account for two-thirds of workers earning less than the living wage and receiving only 80% of their usual salary through the Job Retention Scheme could push these women into poverty. The high rate of furlough among young women also puts them at greater risk of redundancy when the Job Retention Scheme comes to an end this month. Indeed, a quarter of pubs and restaurants have said they will not survive the winter.

The risk of redundancy is heightened by the limitations of the Job Support Scheme which is less generous than the previous scheme and also stipulates that jobs have to be ‘viable’. While viability in this context is yet to be defined by the UK Government, this will likely have implications for jobs in businesses and sectors that remain shutdown, or most impacted by social distancing. Close the Gap is also concerned that part-time workers, of whom women account for the majority, will be disproportionately negatively impacted by the new scheme. Retaining two part-time workers is ultimately more costly than retaining one full-time worker on the scheme. The Job Support Scheme arguably disincentivises employers paying low-paid workers in low-skilled jobs for hours they aren’t working. This could lead to moreredundancies among low-paid workers, particularly as recruitment and training costs are lower in the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, including retail and hospitality.

Women, particularly lone parents, have also been disproportionately affected by the need for more unpaid care, impacting their ability to do paid work. Women in the gig economy have been ineligible for either of the UK Government’s financial support schemes and women in casualised and precarious work face difficulties reconciling variable hours with caring responsibilities. As a consequence, women are leaving the labour market in order to care, or because they feel unsafe, with obvious implications for women’s earnings. In the longer-term, being out of work has scarring effect for women’s financial stability and career prospects.

This is the exacerbation of an existing trend. Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, young women were concentrated in low-paid, precarious work and were already more likely to be experiencing poverty. Women who were already struggling are now under enormous financial pressure with COVID-19 creating a perfect storm for a rising tide of poverty among young women.

Many of the sectors where young women are concentrated, such as retail and hospitality, which are those which have been affected by shut downs and physical distancing measures, are notoriously low paid and characterised by job insecurity. For example, four in ten of those working in retail and wholesale are paid less than the real Living Wage and 80% of people working in hospitality reported that they were already struggling with their finances before going into lockdown. Young women in these low-paid, high-risk sectors were already more likely to be experiencing in-work poverty and are therefore less likely to have savings to fall back on. For women who have had their hours reduced, the loss of earnings will have a profound impact on their financial security.

The automation of work in retail and hospitality jobs is already evident, and as these sectors are less likely to bounce back following the end of the crisis, the impacts for young women workers in these sectors will be long-lasting.

Young women need targeted support to enable them to re-enter the labour market and to secure good quality, sustainable employment. However, despite the well-evidenced impacts of COVID-19 on young women’s employment, we continue to see gender-blind response measures that further entrench young women’s poverty.

One of the policy asks for Challenge Poverty Week relates to the scope of the Scottish Young Person’s Guarantee. Certainly, the design of the guarantee is vitally important in determining if the scheme will benefit both young women and young men. Without a gendered approach, which recognises the barriers young women face in the labour market, the Scottish Young Person’s Guarantee will entrench occupational segregation, exacerbate women’s poverty and widen the gender pay gap.

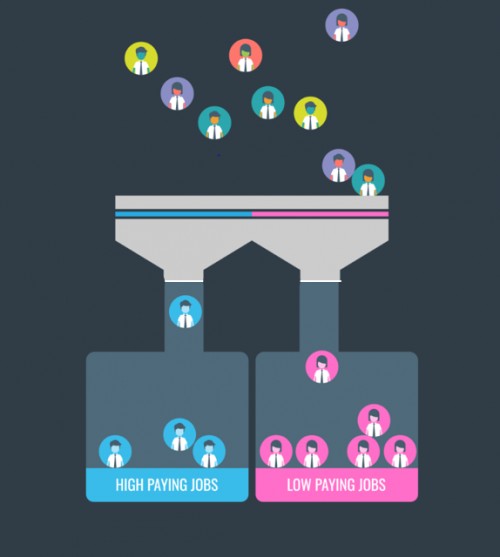

Evidence highlights that generic employability and skills programmes reinforce women’s labour market inequality. The Young Person’s Guarantee must therefore challenge occupational segregation by design so as not to funnel young women into low-paid, female-dominated work which will merely reinforce their higher rates of poverty. The payment of the real living wage for all participants is also critical to addressing women’s higher rates of in-work poverty, and tackling the disproportionate risk of poverty among young mothers.

Flexibility, including offering jobs on a part-time basis, is vitally important to enable women with caring responsibilities to access the scheme. Young mothers are a priority group within the Scottish Government’s Economic Implementation Plan and identified as being at particular risk of poverty in the Government’s Child Poverty Delivery Plan. The Delivery Plan notes that young women with caring responsibilities face a range of barriers to accessing quality employment; to staying in work; and progressing within employment, leading to their concentration in low-paid jobs and sectors. Unless the job guarantee actively challenges occupational segregation by design and embeds flexibility within the scheme, it is likely that the guarantee will reinforce young women with caring responsibilities concentration in low-paid jobs and sectors, potentially trapping women and their children in poverty.

In addition to the substantial impact on young women’s employment and career prospects, recent evidence has also highlighted that young women are bearing the brunt of the UK’s second wave of coronavirus infections. Analysis of hospital records suggest that younger women are now more exposed to the virus, with a substantial rise in the number of women aged 20-40 admitted for serious coronavirus infections since August. This rise is driven by younger women being more likely to be in jobs that leave them vulnerable to infection, including work in pubs, cafes, shops, and the care sector.

Addressing the inequalities women face at work must be a core aim of economic recovery measures, with a particular focus on young women. Recovery must focus on transformational change to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 and advance women’s equality.

A key message of Challenge Poverty Week is that we can work together to redesign our economy so that it works for everyone. As highlighted in Gender and Economic Recovery, jointly published by Close the Gap and Engender, new approaches to our economy are essential if we are to tackle women’s poverty and persistent inequality in the labour market. Putting care and solidarity at the heart of our economy can build an economy that works for women, as well as men, and will create better jobs, better decision-making and a more adequate standard of living for us all.

We are recruiting new trustees to our board!

We are looking for new people to join our fantastic board of trustees.

Committed to women’s labour market equality, you’ll have the ability to think strategically and creatively, and to respond to the needs of the organisation. You’ll also be able to commit the time to fulfil the role of trustee, and help us meet our strategic objectives.

Close the Gap is strongly committed to equality, and recognises that diverse boards are more effective, and result in better governance practice. We would particularly welcome applications from Black and minority ethnic people, disabled people, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people who are currently under-represented on our board. We’re also particularly interested in receiving applications from people that have knowledge and experience in finance and fundraising.

How to apply

The deadline for applications is Friday 9 October 2020.

You will be notified by Monday 26 October 2020 if you have been selected for interview.

It is anticipated that the interviews will take place remotely during the week commencing Monday 2 November 2020.

Our joint response to the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery report

Close the Gap and Engender have published a joint response to the report of the Advisory Group on Economic Recovery (AGER), which was convened by Scottish Government to provide advice on Scotland’s economic recovery once the immediate emergency has subsided. Specifically the group was tasked with advising on measures to support different sector and regional challenges the economy will face in recovery; and how business practice will change as a result of Covid-19, including opportunities to operate differently and how Government policy can help the transition towards a greener, net-zero and wellbeing economy.

Close the Gap submitted evidence to the AGER, along with the set of nine principles for a gender equal recovery, developed jointly with Engender, and endorsed by national women's and single parent organisations.

In our response we highlight that, despite the wide-ranging evidence and advocay around the gendered issues of the economic effects of Covid-19, the AGER's report is not gendered. Despite the profoundly gendered nature of the crisis, which has impacted female-dominated sectors and substantially increased women’s unpaid work, the report barely mentions these as concerns. Its analysis does not integrate these gendered issues and nor is there any evidence of them in the recommendations it has produced.

There is a significant risk that without mitigating action, an economic recovery based on the AGER recommendations will worsen women's labour market equality, women's economic position, and widen income and wealth gaps. Close the Gap and Engender set out key issues for Scottish Government to consider when developing its response to the report. The following areas are of particular concern to Close the Gap's work:

- The care sector review should also

include developing action to address the undervaluation of the predominantly

female workforce. The

challenges around recruitment and retention of the care workforce cannot be

viewed in isolation from the gendered experiences of working in the care sector.

Women care workers are undervalued, underpaid and underprotected in an

increasingly precarious employment landscape.

The review should integrate an understanding that a valued, fairly remunerated

workforce in secure employment is a necessary step in delivering good quality

care services.

- The acceleration of fair work should

also mean fair work for women. Fair work is important in an increasingly precarious labour

market but realising fair work for women means recognising women’s higher

levels of employment precarity,

their concentration in low-paid work,

and the gendered barriers to flexible working

to enable women to balance work with their caringrole.A Centre

for Workplace Transformation must be gender competent, take a gendered

approach, and prioritise the increasing precarity of women’s employment and the

undervaluation of women’s work. Addressing undervaluation is necessary to

address women’s and children’s poverty, and to tackle the gender pay gap.

- Skills interventions should work to reduce occupational segregation as a central aim. Gender-blind skills initiatives entrench the gender segregation that characterises Scotland’s education and skills pipeline.Occupational segregation drives the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on women’s labour market equality, and is a key factor in the disproportionate level of unemployment women, especially Black and minority ethnic women and young women, have experienced, and are anticipated to experience in the future. Occupational segregation also contributes to sectoral skills shortages, and is a drag on growth. Upskilling and reskilling initiatives should be gendered, and aim to reduce occupational segregation. There should also be sufficient flexible places in colleges and universities to enable women to combine learning with caring roles.

- In-work training programmes should be informed by women’s experiences of training in the workplace. There is evidence that women are less likely to have access to training, particularly women working in low-paid part-time jobs, less likely to undertake training that will enable them to progress or secure a pay rise, and more likely to have to do training in their own time and to contribute towards the cost. The expansion of the Flexible Workforce Development Fund should target the effective utilisation of women’s under-used skills, reduce occupational segregation, and gather gender-sensitive sex disaggregated data on learner participants including the types of courses undertaken.

The leaky pipeline of education policy – a look at the DYW strategy

The COVID-19 crisis has changed society immeasurably. The closure of nurseries, schools, colleges and universities means a generation of children and young people are thrust into completely new learning environments and expectations, with teachers, lecturers and other education practitioners delivering learning support in new and challenging ways.

Close the Gap has been working on education and skills policy for many years and we are keenly aware of the impact of this crisis. We are aware that the rapidly changing labour market will mean that those young people emerging from further and higher education to seek employment will face a significant challenge. Young people bore the brunt of the Great Recession. With young women facing inequality from the moment they enter the labour market the impact of the expected post-coronavirus recession is likely to have a chilling effect on their ability to enter and progress in good-quality work.

We know the COVID-19 crisis is already disproportionately impacting women, from their over-representation in key worker roles, the majority of which are low-paid and undervalued, to the challenges of balancing working with delivering unpaid care to children and older or sick relatives. Our recent report Disproportionate Disruption: The impact of COVID-19 on women’s labour market inequality identified that young women are more likely to work in sectors which have shut down and in low-paid roles, placing them at an increased risk of poverty. These inequalities did not arrive with the coronavirus; gender inequality has been stubbornly entrenched in our society for generations.

It's time to focus on gender inequality

Deprioritising women’s and girls’ inequality at this time is not an option. The need for a sharper focus on its causes and solutions has never been greater. Despite policy aims of tackling gender inequality, progress remains out of reach. But why is this? Why, when we have the evidence, when we know what action is needed, are we still so far from real equality for women and girls?

Gender experts have long talked about the cyclical nature of gender inequality and its presence and impact at every stage of life for girls and women. This is why, in 2014, we welcomed the launch of the Developing the Young Workforce Strategy, which was framed as taking a ‘pipeline approach’ and set out equality as one of its five key focus areas. The strategy came with a series of recommendations for stakeholders covering the journey of children and young people from school through to employment, to be implemented over the course of seven years.

In 2019, five years into the DYW implementation plan we undertook a review of the strategy to examine its action on gender inequality in education, skills and careers guidance, and to identify positive outcomes for girls and young women. This review extended to over 200 documents connected to the work of strategy partners and resulted in over 20,000 words of gender analysis. We have recently published a summary of the review and its findings in a more digestible 12 pages.

Commitments to action from Scottish Government

We used the

findings from the review to advocate that Scottish Government and other

delivery agencies take a gendered approach in DYW implementation. We’ve worked

with Scottish Government officials leading the practice and improvement

evaluation of the equality outcomes of DYW, one of the actions in A Fairer

Scotland for Women, to share learning from our gender review.

We’re very pleased to say this has resulted in strong commitments to accelerate action in the final years of the strategy’s work. The most recent progress update from Scottish Government commits to work with Close the Gap to:

- Develop a strategic approach to building gender competence in teachers and other education practitioners;

- Ensure the DYW Regional Groups review is informed by gender expertise;

- Develop guidance for employers engaged with DYW on tackling gendered occupational segregation, and build capacity on the importance of gender equality at work in realising the ambitions of DYW; and

- Ensure any new resources developed for teachers and careers practitioners are gender-sensitive and include guidance on tackling gender stereotyping and segregation.

We also recognise that the COVID-19 crisis will have a significant impact on girls and young women currently in or about to leave education. It is essential that future work under the DYW strategy, and on Scotland’s economic recovery planning, responds to this gendered challenge. We will be working with Scottish Government to ensure this is considered as part of its work on COVID-19.

We also welcome the commitment from Skill Development Scotland in its new Career Information Advice and Guidance Action Plan to roll out mandatory training for career practitioners to build their gender competence and to undertake focused work on gender stereotyping with school pupils and parents. Close the Gap has been calling for this for a long time.

Why we need this action

Our review highlights real and pressing concerns regarding the lack of positive outcomes delivered for girls and young women thus far. We found that there has been no substantive action on gender under the strategy, with the majority of activity limited to generic ‘equalities’ focused work which is unlikely to create change. The evidence suggests that work to address gender stereotyping and segregation is inconsistent and not being prioritised. This indicates the strategy’s commitment to embed equality throughout its work has not been realised.

The reporting of work under the strategy can accurately be described as ‘labyrinthine’, with the large number of stakeholders and inconsistent reporting format making it extremely difficult to identify examples of action on gender inequality. This unclear reporting was further exacerbated by the inappropriate progress indicators set at the strategy’s outset. These issues have combined to create a lack of accountability for stakeholders on gender equality.

The two strongest areas of the strategy relate to colleges and apprenticeships. Each of these areas have action plans which focus on gender and equality more broadly, but this has not translated into meaningful progress for girls and young women. In colleges a lack of focus on infrastructure and the culture change needed in organisations remains and in apprenticeships there has been no progress on gender segregation.

We feel that progress has been critically impeded by a lack of actions for schools and employers. In schools we identified that resources developed for teachers and careers practitioners are gender-blind and are unlikely to provide an impetus for action. This is a significant concern as teachers and careers practitioners have told us that they need support to build their gender competence if they are to challenge gender inequality in their work.

At the other end of the pipeline, the recommendations for employers do not engage with gender or equalities at all. This lack of focus on the employer role in tackling gender inequality means that whatever progress is made throughout the education pipeline, young women will still be entering an unchallenged and unchanged labour market and workplace culture.

Moving forward

While the strategy’s pipeline approach provides a range of opportunities for targeted action to tackle the barriers which hold back young women and girls from benefitting from their full potential, it is unsustainable if each stage of the pipeline does not include concerted action to tackle gender segregation. We know that gender stereotyping begins from birth and is further embedded at each stage of the life cycle. If we continue to take a gender-blind approach and fail to build gender competence in those who are in a position to create change, then change will remain elusive for girls and young women.

We strongly welcome the engagement of Scottish Government and other agencies with the findings of our review. We’re looking forward to working with Scottish Government and Skills Development Scotland to drive real change for girls and young women. These commitments are more important than ever if we are to move the needle on gender inequality in education and skills, and to look forwards to advocate for a gendered response to the emerging challenges of the current crisis.

Free webinar on gender and economic recovery

Following the publication of our 9 principles for an economic recovery that work for women, Close the Gap and Engender are hosting a webinar to discuss how to ensure that Scotland's economic recovery does not leave women behind. The webinar is free and you can register here.

The coronavirus crisis is having a disproportionate economic impact on women, whose work is work is systematically undervalued in the economy, including work that is critical to the Covid-19 response such as health and social care, retail and cleaning. The cumulative impact of the crisis will push many women into further and deeper poverty.

In the webinar our Executive Director, Anna Ritchie Allan, along with Engender's Executive Director, Emma Ritch, will be talking through the principles and there will be space for discussion on how to ensure Scotland's economic recovery is gendered.

The webinar will be held via zoom, and information for joining will be sent on the day of the webinar.