Blog

Findings from the evaluation of the Equally Safe at Work pilot

Yesterday Close the Gap held an online event to celebrate the success of the Equally Safe at Work pilot and launch the evaluation report for the pilot.

Equally Safe at Work is an innovative employer accreditation programme that was developed to support the local implementation of Scotland’s Equally Safe Strategy. The programme was designed to support councils to understand how gender inequality and violence against women (VAW) affect women in the workforce and the wider organisation, and to provide a framework to drive change.

Equally Safe at Work was piloted in seven councils between January 2019 and November 2020. The pilot councils were Aberdeen City, Highland, Midlothian, North Lanarkshire, Perth and Kinross, Shetland Islands and South Lanarkshire.

Four of the pilot councils received bronze accreditation. All the councils received pilot accreditation to recognise their important role in piloting Equally Safe at Work and in generating key learning that will shape the future development of the programme.

To receive bronze accreditation councils had to demonstrate they had met criteria across six standards which align with women’s workplace equality:

- Leadership;

- Data;

- Flexible working;

- Workplace culture;

- Occupational segregation; and

- VAW.

What the evaluation told us

Over the pilot period, we collected qualitative and quantitative data to measure whether the programme was effective at improving employment policies and practice and, also in improving understanding about gender inequality and VAW in the workplace. We also wanted to pilot whether an employer accreditation programme was an effective model for engaging with councils.

The evaluation found that councils had developed improved employment policies and practices. As a result of engaging with Equally Safe at Work councils:

- developed VAW policies and introduced support mechanisms for victim-survivors;

- reviewed and updated equality policies to include information on occupation segregation, VAW, sexism, misogyny, and intersectionality;

- reviewed employment policies to ensure they are gender- and VAW- sensitive;

- updated flexible working policies to ensure the needs of different groups of women, including victim-survivors, are met;

- provided training to line managers on flexible working and VAW;

- supported quantitative and qualitative data gathering on employees attitudes and behaviours around gender equality and VAW, and experiences of working in the council;

- reviewed practice on progression, recruitment, and development to ensure it addresses the barriers women face;

- developed improved data gathering systems to capture the experiences of different groups of women in the workforce;

- developed systems to collect data on flexible working, disaggregated by gender;

- developed initiatives to address occupational segregation; and

- delivered internal awareness-raising campaigns on VAW and gender inequality.

The evaluation also looked at whether councils had an improved understanding of gender equality and VAW, and an improved understanding of the employer role in prevention. Key findings include:

- There was an increase in the extent to which employees disbelieved myths about VAW;

- Line managers felt more confident about recognising the signs of VAW and responding to disclosures or reports;

- Councils demonstrated leadership to staff to challenge VAW through statements from the chief executive and council lead;

- Women’s confidence in report and disclosing VAW remained the same;

- While there were high numbers of experiences of VAW, very few formal reports were made to councils; and

- There is a continued need to develop capacity in line managers and build trust in the reporting process.

There was minimal change in attitudes and behaviour towards gender equality. This was anticipated given the difficulty in creating attitudinal and behavioural change in a short period. Longer-term attitudinal and behavioural change in the workforce requires leadership commitment to challenge workplace cultures which sustain gender inequality and prevent VAW.

Success and challenges

Four councils received bronze accreditation and completed the pilot. To demonstrate they had completed the pilot, councils submitted a range of evidence to be assessed by Close the Gap for the bronze tier. Councils found criteria in the sections on data, occupational segregation and workplace culture most difficult to complete. As well, some of the evidence that was submitted was not adequately gender-sensitive which suggests that there is further work required to build gender competence in councils to better understand the importance of gender and VAW-sensitive employment practice.

Equally Safe at Work as a driver of change

The Equally Safe at Work pilot has been effective in engaging with councils on VAW and gender equality and has enabled positive changes to employment practice which contribute to the advancement of women’s equality. The programme has built capacity in councils to better understand, respond to, and prevent VAW. It has also enabled councils to progress work on gender equality by developing improved employment policy and practice; gathering data that are critical to gender equality at work; and developing initiatives to address occupational segregation.

A key success factor of Equally Safe at Work is the prescriptiveness of the programme. Councils were provided with clear and specific guidance for improving employment practice across six standards, including best practice examples. Through this approach, councils were able to make changes to employment practice, build capacity in line managers and others, and challenge harmful stereotypical attitudes and behaviours. Learning from the pilot also highlighted that for councils to be successful in the programme, it is critical that there is commitment from senior leaders, adequate resources to deliver the work, and crucially, an understanding of, and a commitment to, ending VAW and advancing gender equality at work.

You can read the full report here.

Celebrating the Equally Safe at Work pilot councils

We are delighted to announce that Aberdeen City Council, Midlothian Council, North Lanarkshire Council and Shetland Islands Council have been awarded bronze accreditation for the Equally Safe at Work pilot.

We also want to congratulate all the councils who participated in the pilot for their great work on Equally Safe at Work. All councils have received pilot accreditation which recognises their important role in gathering key learning on local government employment practice that will shape the future development of the programme.

Equally Safe at Work is an innovative employer accreditation programme that was developed by Close the Gap and piloted in seven local authorities from January 2019 until November 2020. The pilot councils were Aberdeen City, Highland, Midlothian, Perth & Kinross, Shetland Islands, North Lanarkshire and South Lanarkshire.

Equally Safe at Work was developed to prevent violence against women and advance women’s labour market equality in Scotland through working directly with employers to ensure that workplace policies and practice take account of women’s experiences of employment. The programme has proven to be an important lever in enabling councils to take substantive action on gender equality and demonstrate leadership on violence against women. As a result of the pilot, the early adopter councils have implemented a number of important changes to the workplace including developing initiatives to address occupational segregation, developing violence against women policies and improved data gathering systems on employee experiences of violence against women, and other aspects of gender inequality.

You can read more about the successes from the pilot here.

COVID-19 has put health and safety at the heart of fair work, but women’s needs remain under-researched, under-reported and under-compensated

COVID-19 has brought new emphasis to the danger of occupational exposure to disease and injury, leading to increasing focus on health and safety concerns within the context of fair work. These concerns are particularly important for women who account for the majority of key workers, meaning they have greater exposure to the virus in the workplace.

Figures from the HSE covering the period of April to September 2020 found that 75% of employer COVID-19 disease reports made in Scotland related to a female employee. Evidence also shows that women aged 50-60 are at greatest risk of long-COVID and women were twice as likely as men to suffer from COVID symptoms that lasted longer than a month. Many women, therefore, will be struggling to return to work due to the effects of Long-COVID.

Women account for 98% of key workers earning “poverty wages”. Many women with greater exposure to the virus and increased likelihood of long-COVID are therefore less likely to have savings to fall back on. It is therefore pivotal that these women are able to access industrial injury benefit to prevent them, and their families, falling into further and deeper poverty.

However, the current system of employment injuries assistance (EIA) does not deliver for women in the labour market. Women account for only 16% of those claiming Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit (IIDB) and only 13.5% of all new claims to the benefit in the ten years up to December 2019 were made by women.

Mark Griffin MSP’s proposed Scottish Employment Injuries Advisory Council Bill is therefore a critical, and timely, intervention. The Bill aims to establish an advisory council on workplace injuries and diseases to scrutinise social security legislation in the realm of EIA and commission research into new employment hazards and entitlements. The consultation document establishes that a key priority for change should be research into women’s experiences of industrial injury and the development of new mechanisms and definitions which improve women’s access to industrial injury benefit.

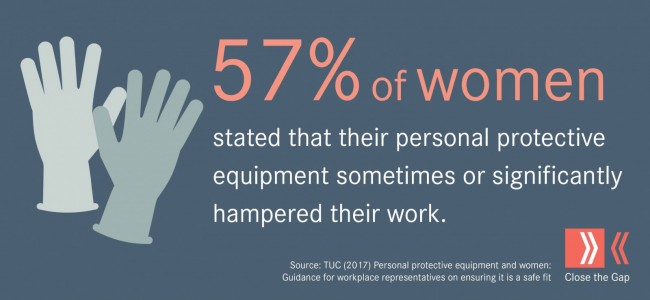

The modernisation of the EIA system and increased focus on women’s health and safety is long-overdue. Women’s experience of injury and disease are routinely ignored in Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) design. A recent TUC survey found that 57% of women found that their PPE sometimes or significantly hampered their work and only 29% of women said that the PPE they use is specifically designed for women, meaning that it is not fit for purpose. This is a significant health and safety issue, as the wrong PPE can increase risk from injury or disease. For instance, ill-fitting gloves can lead to problems gripping, while the wrong shoes or overalls can increase the chances of tripping. Despite this heightened risk of injury and disease, the EIA does not respond to women’s needs.

Issues around a lack of appropriate PPE have been further highlighted during the pandemic. The Royal College of Nursing have raised particular concerns around access to PPE for staff working outside of a hospital environment, and there have been widely reported concerns around access to PPE for social care staff, 85% of whom are women. Inappropriate PPE can leave woman further exposed to COVID-19, posing a severe risk to the safety of women workers and their families.

A lack of research into women’s health and safety means that many female-dominated jobs and sectors, and certain conditions predominantly experienced by women, continue to be absent from the list-based system which determines compensation eligibility under the current scheme. The prescribed list is focused on the injuries and illnesses most associated with male-dominated jobs and sectors, such as construction, and neglects those risks associated with low-paid, female-dominated sectors such as cleaning and care. Examples of diseases and injuries commonly experienced by women which are not considered by the current scheme include MSDs through lifting, breast cancer caused by shift work, and asbestos related ovarian cancer.

Women still typically have the dual burden of household work and caring responsibilities which exposes women to the similar hazards at home they experience at work, increasing the likelihood of injury. However, the mechanisms for accounting for this unpaid work are insufficient in the current scheme which ultimately does not recognise the realities of women’s lives. The factors which complicate the process of establishing eligibility, including women’s propensity to work multiple jobs and to have career breaks in order to care for children, create a further barrier to women’s access to support.

Overall, it is clear why the TUC have concluded that less attention has been given to the health and safety needs of women. Research and developments in health and safety regulation, policy and risk management are primarily based on work traditionally done by men. By contrast, women’s occupational injuries and illnesses have been largely ignored, under-diagnosed, under-reported and under-compensated.

The modernisation of EIA and improvements to the system are long overdue, and reform is now a matter of urgency due to the workplace implications of COVID-19. Female workers face significant challenges in receiving support through the current system which is ultimately unfit for purpose. This adds to the undervaluation of “women’s work”, with a lack of recognition afforded to the risks and skills associated with women’s work. The current approach to IIDB takes the male worker as standard, leading to a system which has neglected women’s health and safety requirements and erected barriers to compensation.

You can read our full submission to the consultation on the Scottish Employment Injuries Advisory Council Bill here.

Gender equality can help employers to weather the Covid-19 storm

Women’s employment has been hit hard by Covid-19 and it is highly likely that there may be a loss of female talent in the workplace if employers don’t act to support their female staff. This could drive up costs, including recruitment, training and the loss of experienced staff.

We've developed new guidance for large companies, alongside guidance for SME employers, on supporting women in the workforce during Covid-19. The Close Your Pay Gap guidance for large employers can be downloaded here. Our Think Business, Think Equality guidance for SMEs can be downloaded here.

Both contain practical and easy-to-implement actions that employers can take to ensure their employment practices and return to work plans are gender-proofed. Line managers have a huge role to play in supporting employees and this guidance will help them to understand and respond to the specific experiences of women workers during the pandemic.

A recovery that works for women works for employers

Supporting women at work doesn’t just benefit women - it benefits employers too. The business benefits of gender equality are well-evidenced, driving improved business performance and economic growth. In the run up to the April 2021 gender pay gap reporting deadline companies may not realise the potential for Covid-19 to widen their pay gap. Our new guidance provides good practice actions that employers can take now to help prevent this happening and even close their pay gap in the process.

Supporting women workers will also help support the resilience, recovery and regrowth of companies and businesses across Scotland. This benefits all of us.

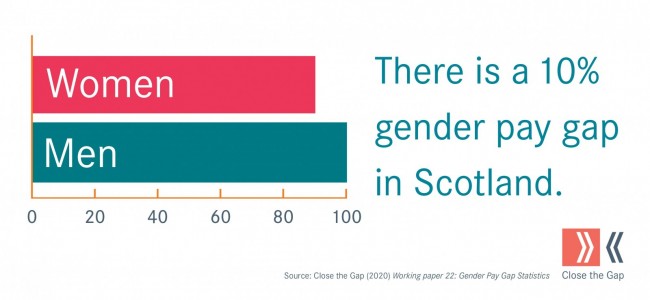

The Gender Pay Gap Manifesto: the 2021 Scottish Parliament elections are an opportunity to realise fair work for women

Close the Gap have now published our manifesto for the 2021 Scottish Parliament election. The Gender Pay Gap manifesto outlines 14 policies that should be adopted over the next parliamentary term to address the gender pay gap and realise fair work for women. In line with the multiple causes of the gender pay gap, the policy priorities cover early learning and childcare, automation, the public sector equality duty, employment practice, occupational segregation, low pay, skills policy, tackling the undervaluation of “women’s work” and economic development.

The focus on the gender pay gap in the Scottish Parliament has never been sharper, yet we are still very far from meaningful progress on the inter-related barriers women face in entering and progressing in employment. Fair work has also been established as a key policy focus for all parties represented in the Scottish Parliament, but fair work has to mean fair work for women as well.

It is often repeated that as employment law is not devolved to Scotland, it is

not possible for the Scottish Parliament to address the causes of Scotland’s

gender pay gap. Our manifesto highlights that this is untrue. The majority of

the causes of the gender pay gap are not unlawful, and therefore sit outside of

the scope of employment law. Instead, action is required in a number of policy

areas over which the Scottish Parliament has the power to enact change now. Some

of Close the Gap’s key policy calls include:

- Designate childcare a key growth sector, along with social care, to recognise care as vital infrastructure.

- Ensure action to address the undervaluation of “women’s work”, including in adult social care and childcare, is core to labour market and economic recovery policymaking in response to COVID-19.

- Support the employer accreditation programme Equally Safe at Work through continued funding.

- Deliver a further extended funded childcare entitlement equivalent to 50 hours a week to enable women to work full-time.

- Recognising the link between women’s poverty and child poverty, prioritise substantive action to tackle women’s low pay in addressing child poverty.

Taking substantive action on women’s labour market inequality will enable the Scottish Parliament to realise the ambitions of fair work and inclusive growth. Women’s inequality in the labour market is a drag on economic growth and productivity, and occupational segregation is correlated with sector skills shortages. Research by Close the Gap has highlighted that closing the gender gap in employment is worth £17 billion to the Scottish economy.

Transformational change is needed to close the pay gap, and it is time for meaningful, and substantive action on the causes of the gender pay gap in Scotland. Across the political parties, there was a lack of specific policies relating to the gender pay gap in the manifestos for the 2016 Scottish Parliament election and there were also very few policy commitments on gender equality.

The 2021 Scottish Parliament elections present an opportunity for political parties to show leadership on gender equality and take the bold action that is needed to realise fair work for women. Action on women’s labour market inequality has been rendered even more pivotal by the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. The social, economic and labour market impacts of COVID-19 have the potential to reverse gender equality gains and exacerbate women’s pre-existing inequality. We think it is time for cross-party support for closing the gender pay gap in Scotland.

Over the next few weeks, we will be highlighting our specific policy asks over on our social media. In the build-up to the election in May, we will also be continuing to work with political parties and MSPs to encourage support for these policy asks.

You can read the full manifesto here.